s too much up-front investigation ever too much? Predicting the behavior of a future launch is the secret sauce of most businesses, yet it is far from being a precise science.

In this quest, how much up-front investigation you do and how long you keep spinning the questions can be a counterproductive use of time and can cost way too much money. Plus, odds are that it will be more demanding than a simpler and more focused early-stage investigation. Very few cases would deserve such a heavy approach and odds are that your case is not one of them.

Killing it softly

The innovative marketer’s dream is to have an “open tap” with the organization; “carte blanche” for unlimited resources to use and test whatever is needed at any point in the process. In other words, a 3-5 year development timeline, dozens of different versions of same plan and a realistic implementation that may fall short of the expectations.

But when a long process comes to a point of closure, it would probably still reflect many uncertainties around the known killer points (holding on to desired pricing, margins, sales forecasts, insights, product performance, etc.) that one could wonder, what is the point of all this? And we all know that in a heated pre-launch scenario, it would take only a big disaster to “stop the engine”.

What results is major pressure coming from the top down, compelling agencies and sales teams to be completely focused on the launch itself. Reflection only starts during the post-launch review phase. Then slowly (and silently) but surely, other projects get prioritized to cover up for the big miss. You know where this (never) ends. This insanity has got to stop.

Source: David Armano: Conventional Marketing

Is the classic approach to be blamed?

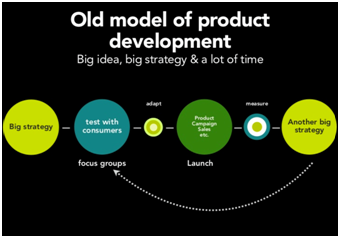

The conventional model is not wrong. Everyone would agree that strategy comes first and is then followed by testing, validation and scaling up. But many organizations are just systematically killing the ability to innovate by showing an extreme appetite for modeling the business outcome with lots of validation steps at the expense of just answering the killer points of the project right at the beginning. The framing of the big issues is consistently neglected.

In spite of good experiences inside reputable companies, people seem to get lost on details that might look good when presented but are less relevant for properly predicting if a) the team truly has a big idea on its hands and b) the company has what it takes to execute. The validity of a model can only be judged on how well it produces results. Now there seem to be enough bad experiences to prompt bigger organizations to at least reassess how things are done, particularly for those projects that are actually true innovations.

In these cases, a surprisingly large number of companies have already realized that they are just not good enough to develop ideas in-house and prefer to source them from smaller competitors. Or, they simply produce an old fashioned copy when these new launches become successful enough to start bothering the big fishes in the pound.

Properly incubate ideas in early stages

Everyone dreams about launching something big. The real innovations are just so different that we recognize them from a mile away. Real innovations are those things that can cause sales to skyrocket, attract a whole new range of consumers, change value perceptions, impact the equity of a brand and challenge existing manufacturing capabilities. They basically have some unknowns that are so big that the only upfront certainty is that the business team will need to think a lot harder to crack it. But these innovations just don’t happen by chance.

A long sequential approach will actually prevent the necessary breakthroughs in thinking, which are the most precious contribution from the business team; these are breakthroughs that can’t simply be flip charted in a fancy “kick off” workshop.

The down the hill path. Or death spiral

More often than anyone will admit, the symptoms of a death spiral are expressed by the doubts: “Have we jumped into the execution too fast without properly addressing the key points?” or “It feels like we never manage to evolve beyond the initial exploration phase.”

In either case, the result is that actions are taken, the scope starts spinning out of control and resources start sinking. After the third or fourth validation step down the road, the odds are that many members of the team are new. The good ideas and assumptions that were nurtured in the beginning of the project are probably almost entirely neglected already and the project doesn’t look nearly as promising as it was in the beginning. When this happens, the project is either deprioritized or goes humbly back to the drawing board.

A lean solution: Concept phase should be hypothesis driven

If we observe what the successful start-ups are doing, we see that they excel in reality checks and fast iterations. As simple as that might sound, this fresh approach towards innovation is outpacing the bigger companies with deep pockets when it comes to their ability to truly conceive bold new launches.

Steve Blank describes this in a very good article published in May of 2013 in HBR (Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything) . He discussed how, when compared to implementation driven corporations, the start-ups have so many “unknowns” when they start that their primary concern is to quickly assess, validate and re-state the assumptions until they believe they are on to something tangible. He draws a comparison between a “lean” and a traditional way to innovate, which clearly illustrates why so many companies are just spinning instead of truly innovating.

Break the cycle: First get to the main assumptions. Clarify them.

Considering the resources that more structured companies have, they should be able to combine experience, talent and a way of managing innovation that yields better results. The “grey haired” and talented people must work smartly during the concept phase and use sound judgment to reach a meaningful conclusion within a few months. This “proof of concept” is not a fancy wheel in a PowerPoint slide; it is an early business assessment about the main business assumptions surrounding the launch. The best way to tackle this task is to define and run experiments to generate the necessary learning during the concept phase.

However, even when companies follow this approach, they often get it wrong because they apply the wrong filter to the situation. Instead of using it as a learning opportunity, they use it as a small launch or a pilot.

I particularly like the way Stephen Shapiro (Innovate the way you innovate, European Business Review, Jan-Feb 2013) describes what should be the success criteria in this phase:

1. The set of hypotheses are confirmed –> Meaning that a new idea has good potential. Time to chart the project and accelerate development.

2. The set of hypotheses are not confirmed, but we generated other conclusions that show potential as well. –> This is the most likely outcome. Reiterate the experiment and try another round of hypotheses.

3. The set of hypotheses are definitely not confirmed –> Nothing else is noteworthy. Time to abandon the idea and move to the next one.

4. Inconclusive results –> This is a true failure; a waste of time and resources without a clear outcome.

Bottom line

I hope by now you realize that there is enough evidence to show that taking a simpler and objective approach at the beginning of the development journey is the answer to the marketing insanity. It’s about raising and answering the right killer points, preferably through real experimentation.

This reality check and the associated iterations would enable business teams to reach meaningful conclusions very early in the process. That is early enough to calibrate, redirect and begin a fast track development. This is a much less risky approach and definitely a more successful one.